In late October 1945, Jean-Paul Sartre delivered a lecture in Paris at the Club Maintenant entitled Existentialism Is a Humanism. The lecture was later edited and published in 1946 as a philosophical work of the same name. In this lecture, Sartre introduced the first core concept of existentialism: existence precedes essence.

For Christians, “essence” refers to the mission and purpose bestowed upon individuals by God before their birth. However, regardless of religious belief, philosophers such as Diderot, Voltaire, and Kant all proposed the notion of a shared “human nature.” In their view, human nature constitutes a universal essence common to all people, and each individual is merely a particular manifestation of this universal essence. Sartre and existentialism, however, reject the existence of such a pre-given human nature.

Sartre argues that human beings possess no a priori essence. Instead, he asserts that existence precedes essence: human beings are first thrown into the world, gradually come to understand themselves through their encounters with the world and with themselves, and only then define who they are through their actions and choices. This position is closely connected to Sartre’s inheritance of Cartesian philosophy, particularly his emphasis on the cogito—the idea that the subject emerges through consciousness and self-reflection, rather than through any innate or predetermined essence.

Thus, in Sartre’s view, what makes a human being “human” does not stem from a pre-existing nature or purpose, but from the process of experiencing the world, making choices, and assuming responsibility. Human essence is not given in advance; it is continuously formed after existence, through experience and self-definition.

This essay will therefore use the narrative structure of The Truman Show to illustrate this transformation of the concept of “essence,” and, from an existentialist perspective, further explore the philosophical question of what it means to be human.

1. A Being Thrown into the World

In his lecture, Sartre describes human beings as beings thrown into the world, whose existence carries no inherent or pre-established meaning. Yet this existentialist proposition does not seem to fully apply to The Truman Show. For Truman, meaning is not constructed after existence through his own choices, but rather predetermined before his birth. He is defined as a “person” who grows under the gaze of cameras and audiences, rather than as a subject truly living in the real world.

In this sense, Truman more closely resembles a character placed within a system. His life trajectory, behavioural logic, and even life goals are carefully planned and guided by the enclosed system of the television set. Although his actions appear on the surface to be freely chosen, any “variable” he produces under conditions of deception and manipulation is continuously corrected and optimised by the system, ultimately leading back to a predetermined narrative outcome. Truman’s choices are therefore not genuine acts of freedom, but rather permitted choices within a pre-established structure.

However, this does not mean that the film denies Sartre’s emphasis on absolute freedom or multiple possibilities. On the contrary, before Truman becomes aware of the existence of freedom and choice, his consciousness can only operate within the given framework, passively complying with each arranged action. It is only when Truman gradually realises the falsity of his world and perceives the possibility of freedom and choice that he truly confronts multiple paths of existence and begins to make non-preordained choices that no longer serve the established narrative.

In Sartre’s famous example of the café waiter, the waiter’s understanding of his own essence does not arise from genuine self-knowledge, but from bad faith. By fully identifying himself with the role of “waiter,” he convinces himself that this role constitutes his essence, thereby evading the responsibility and anxiety that accompany freedom.

Yet unlike the tray he carries or the coffee cups upon it, the waiter is not a fixed object. He is not entirely defined by function or utility, but remains a fluid and changeable subject. For this reason, human beings cannot be assigned a stable, a priori essence in the same way objects can. Human existence is always in flux, and human essence can only be generated through experience, choice, and self-consciousness.

For Sartre, self-consciousness is not a static form of introspection, but an ongoing process of interaction between the individual and the self. It is through awareness, denial, or acceptance of one’s own condition that individuals continuously shape their mode of existence. Thus, what makes a human being human is not the role one plays, but the fact that no role can ever fully exhaust the self.

In The Truman Show, however, bad faith does not originate from Truman himself, but is produced and sustained by the world in which he lives. Within the reality-show system, the director deliberately constructs a form of bad faith and disguises it as good faith. Under this disguise, Truman gradually comes to believe in and internalise this imposed belief, accepting his social roles as an ordinary office worker, husband, and citizen.

This acceptance does not result from free choice, but from passive acquiescence to an assigned essence. In this respect, Truman closely resembles Sartre’s café waiter: both identify themselves with fixed roles and unconsciously evade the responsibility of freedom. Although both possess some awareness of their subjectivity, they nonetheless choose to see themselves as stable, unchanging objects rather than evolving subjects. This is precisely why they can temporarily coexist in apparent harmony with a world structured around certainty and predictability.

Because Truman lives within a fully controlled environment, his understanding of his own existence is shaped into an illusion—namely, the belief that he has possessed a fixed and unchangeable essence since birth. In reality, however, the question of who Truman “is” only becomes meaningfully definable once he leaves the fabricated world. If everything he previously experienced was based on deception and fiction, then the self-knowledge and so-called essence formed within that world must also be subject to negation.

In other words, Truman’s previously assumed essence does not emerge from authentic encounters with freedom and reality, but from attachment to a constructed and false reality. As such, this essence lacks existential legitimacy. Only by leaving the fabricated world and confronting real uncertainty and freedom can Truman redefine his existence through his own choices.

2. The Absurd World and Freedom

Truman’s freedom does not begin with action, but with doubt. It is at the moment doubt emerges that Truman first becomes aware of himself as a subject, and the world he faces begins to reveal its absurdity. This awakening does not immediately grant him absolute freedom, but it creates the condition for freedom to become possible.

Human beings constantly seek their “essence,” yet this pursuit is fundamentally a form of resistance against an absolutely absurd world. We cannot accept that our existence lacks pre-given meaning, nor can we accept the world’s silence in response to our demand for meaning. As a result, we attempt to locate a non-existent a priori essence to counter this absence. As Camus argues, the absurd does not reside solely in the world or solely in human consciousness, but emerges from the relationship between the two: humans relentlessly pursue meaning, order, and explanation, while the world refuses to respond. It is this tension that constitutes the absurd.

In The Truman Show, absurdity does not manifest as chaos or disorder, but as Truman’s gradual realisation that the world he inhabits lacks genuine reality. The absurd does not appear at the moment of collapse, but at the moment the world begins to shed its disguise. The director’s and crew’s attempts to manage unexpected incidents function as a metaphor for psychological defence mechanisms—how individuals instinctively preserve the rationality of their existing world when faced with potential threats.

When the stage light labelled as a star falls from the sky, Truman does not interpret it as an ominous sign. Instead, he quickly incorporates it into everyday experience and rationalises it. This reaction echoes Sartre’s claim that the meaning of signs is not inherent, but assigned by the subject. How we interpret an event depends not on the event itself, but on how we choose to understand it (cogito). Through this reconstruction of meaning, Truman temporarily preserves his trust in the world.

Similarly, when Truman hears the production team’s communications through his car radio, he does not immediately recognise the abnormality. Rather, he interprets the incident according to the familiar and stable logic of his daily life. At this stage, the absurd has not yet fully emerged—the world is still barely maintained as something “understandable.”

For Truman, Fiji represents a gateway to the self; for humanity, each of us possesses our own “Fiji.” It is through moving toward this destination that we begin to realise that essence is not predetermined, but must be reconstructed through freedom and choice. The obstacles encountered along the way are manifestations of the absurd—yet it is precisely this absurdity that propels us toward essence.

In the film, once Truman becomes aware of the abnormalities in his world, he attempts to reach Fiji—a place that symbolises the “true self” for him. Fiji’s significance lies not in geography, but in Lauren, the only person Truman truly loved within the constructed world. Guided by this emotional truth, Fiji becomes imbued with the meaning of authenticity and selfhood.

The resistance Truman encounters, however, comes not from a single force, but from the world as a whole: his wife, his friends, and even the city’s transportation system all work to prevent his pursuit of selfhood. These obstacles are not accidental, but deliberate mechanisms designed to preserve the established order.

In this sense, they function as tests of freedom. When individuals submit to such resistance, they enter what Sartre calls bad faith: they choose to believe in a “truth” that no longer needs to be questioned, thereby accepting what should have been resisted. Through rationalisation or denial, individuals abandon the responsibility of freedom and retreat into a world that appears stable but is fundamentally untrue.

3. “To Be or Not to Be”: Freedom, Choice, and Responsibility

Within existentialism, the question of “to be or not to be” does not concern survival alone, but whether one is willing to assume the responsibility that accompanies freedom and choice. For Sartre, human beings are always absolutely free; even the refusal to choose is itself a choice. In this sense, the dilemma Truman faces at the film’s conclusion—whether to stay or leave—serves as a quintessential existential metaphor. It is not about physical departure, but about whether one chooses to confront or flee from freedom.

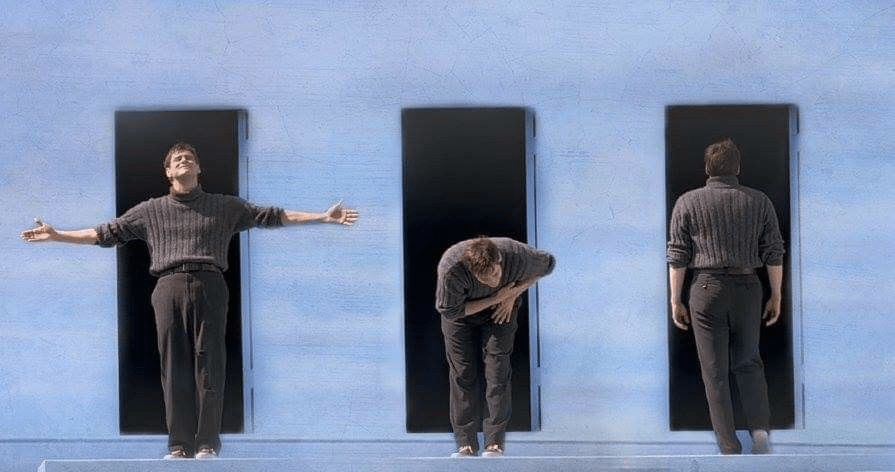

After Truman has overcome all visible obstacles in his life, what ultimately stands before him is not safety, but absolute freedom. The final sequence at sea does not represent mere physical escape, but a profound existential metaphor. The violent waves, the storm, and the fragile boat symbolise the ultimate barriers individuals face in the pursuit of selfhood—forces that compel obedience and self-deception. Once these external obstacles lose their power, what remains is the most terrifying truth of all: freedom itself.

At the film’s end, Truman confronts not merely the exposure of the show but the fundamental truth of human existence. The reality he faces—defined by uncertainty, absurdity, and the absence of guarantees—is the basic condition of being human. What makes Truman “human” is not his fame, visibility, or assigned identity, but his courage to confront uncertainty and accept absolute freedom.

The director’s final revelation—that Truman is a beloved global figure watched by millions—offers him a ready-made identity, one defined entirely by external authority. From an existentialist perspective, this closely resembles the theological notion of essence granted by God: a role imposed before choice and experience. Yet this identity fails to answer Truman’s question, because it is not chosen by him. It is imposed, not generated through authentic existence.

Truman’s decision to leave, therefore, marks the moment he truly becomes human. By rejecting an identity defined by others, he refuses to remain in bad faith and instead embraces the absurdity, uncertainty, and responsibility of freedom. In doing so, he does not discover a pre-existing meaning of life, but begins to create his own. His choice affirms the existentialist claim that what makes us human is not a meaning given at birth, but the meaning we actively construct through our encounters with the world and with ourselves.

4. What Does It Mean to Be Human?

In existentialism, freedom is not a state of liberation, but a responsibility that must be borne. Truman’s departure does not lead to a certain meaning, but to an uncertain yet authentic mode of existence. To be human does not mean possessing a unique essence, but refusing to allow others to choose on one’s behalf. Truman becomes human not because he discovers his true self, but because he refuses to continue living a life defined for him. In a world that offers no guaranteed meaning, choosing to act and to assume responsibility is precisely what it means to be human.

Leave a comment